Guest blogger Mary Louise Marino is a startup social entrepreneur and founder of Indigo Lion Artisan Boutique. Her three-month journey across Southeast Asia and Northeast India is in part to connect with artisan groups, learn about their work, and begin selecting her initial collection for her shop.

Serendipity connected her with village weavers in Thabou and Nayang Tai in Laos, where letting the day unfold put her in the center of figuring out how to be a buyer on the spot.

I met Sin at Ock Pop Tok, a well-established boutique shop in Luang Prabang, Laos, a social enterprise working in both ethnic and contemporary textile designs. When I first walked in the store, his approachable smile and inviting manner made our conversation easy. Sonnalee, the store manager, and Moonoy, the assistant manager, were equally engaging.

It was clear that they all cared about their work, were extremely knowledgeable about the various ethnic groups throughout Laos making the textiles and textile products, and passionate about the social mission of Ock Pop Tok. When I introduced myself and the idea of Indigo Lion Artisan Boutique, Sin invited me to his village to meet women who still weave traditional designs and have finished products, if I was interested to buy. Of course I said yes!

Two days later we met early morning at the bus station for the two hour trip in the back of a

When we arrived in the remote village of Thabou where Sin grew up, the first order of business was lunch. We walked a little ways where his family grows rice and vegetables, and picked up handfuls of fresh greens.

Kitchens are generally outside the homes we’d noticed (much like outdoor camping but more permanent here), so that’s where we headed in Sins’s home. It quickly became a group event. Marie washed the vegetables, Katie chopped them, Sin’s mother Lasoy went off to buy fresh fish, his sister chopped wood kindling, Sin and his niece got the fire started, Sin’s brother cleaned and skinned the fish, his mother grilled it, and Sin boiled the green vegetables in lemongrass and garlic. And me, well, I was the official photographer.

The sense of gratitude to Sin and his family, his mom especially for welcoming us into their home was palpable. Not often do travelers like ourselves get a chance to make the kind of serendipitous connection, where without planning and much fuss do we get a glimpse into the lives of others very much in their homes. Lunch was fantastic, to say the least, and we returned a small gift in kind of fruits and vegetables from the market we picked up later in the day.

The traditional headscarves caught my attention most – deep blue-black indigo with a refined yet simply detailed embroidery that I had never seen before. It had been handspun, hand dyed, handwoven, and hand embroidered by Sin’s mother many years ago.

She placed the headscarf on her head in the fashion of the Tai Dam ethnic group of which Sin and

I wondered what memories came to her in that moment? What was she feeling then of the past, the present, of herself? She seemed pleased, then slightly embarrassed, but she knew we were all appreciative, a special recognition in that moment.

Inquiring more about the textiles, the cotton was grown from nearby farms, as was the raw silk (we visited the silkworms in various stages of production at another woman’s house).

The designs were traditional, referencing the diamond-shaped mahoy seed. The dyes are natural, produced in the village from the indigo plant and macbau, a small fruit plant used for the red.

A little negotiating and I bought two pieces that I could envision as table runners. Pavan seemed most grateful for the sale, eyes watery and her palms pressed together, thumbs touching her forehead, saying khob chai to us, “thank you.” We learned after that her health was not good and the money would help her get treatment.

Padee was waiting for us at the house next door, with an even bigger collection of finished textiles, all beautifully crafted. I had to keep in mind that I was buying for my shop, and that a random assortment of this and that design wouldn’t work, so I leaned in on similar designs of what I just bought. Padee had a gorgeous piece, something Sin said could be a wall hanging in my shop to showcase the Lao Tai Dan style. Great idea, I thought! So I bought it.

Finally, I had to keep my mind on my business when it came to buying, the reason why all of us were there, truthfully. For example: Would it sell. Does it convey a story. Will this evolve into a longer-term buying relationship. What is my budget for today. Are these good prices. Does it fit in my luggage. Can I ship it home. I couldn’t buy a lot, nor did I buy from everyone, being mindful not to buy out of pressure or obligation, which was insanely hard.

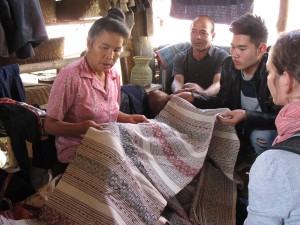

Sin’s friend with a van then drove us 20 minutes to the next weaving village of Nayang Tai, of the Tai Lue ethnic group. One of the traditional homes had a large open room where they received us. One woman, than another, and another started to arrive, then more, eager to show us what they made, and to sell. I guess they got the word out that we had arrived.

Bags upturned and textiles unfurled and displayed on the floor in front of us to see, all so wonderful I didn’t know where to begin. Most of what they showcased were cotton scarves, runners, and napkins in their Tai Leu style. While the style was only slightly different (simpler designs, softer cotton) to the Tai Dam, their resources and processes were similar. Cotton grown from their farm, hand spun and woven, using natural dyes – the indigo plant for the indigo blue, the macbau fruit for the red.

I bought five scarves of varying patterns from Chaban and her daughter, Noy and ten napkins from another woman, Panya, completing my collection.

As usual, I wondered more about the women I was meeting. Conversations translated through Sin

Mary Louise Marino is an artist and entrepreneur who will be formally launching Indigo Lion Artisan Boutique this Fall. All photo’s courtesy Mary Louise Marino. For more information visit: http://indigolionartisanboutique.com/for-artisans/